A look at pandemics and longevity by David Sinclair, Chief Executive, International Longevity Centre UK.

A look at pandemics and longevity by David Sinclair, Chief Executive, International Longevity Centre UK.

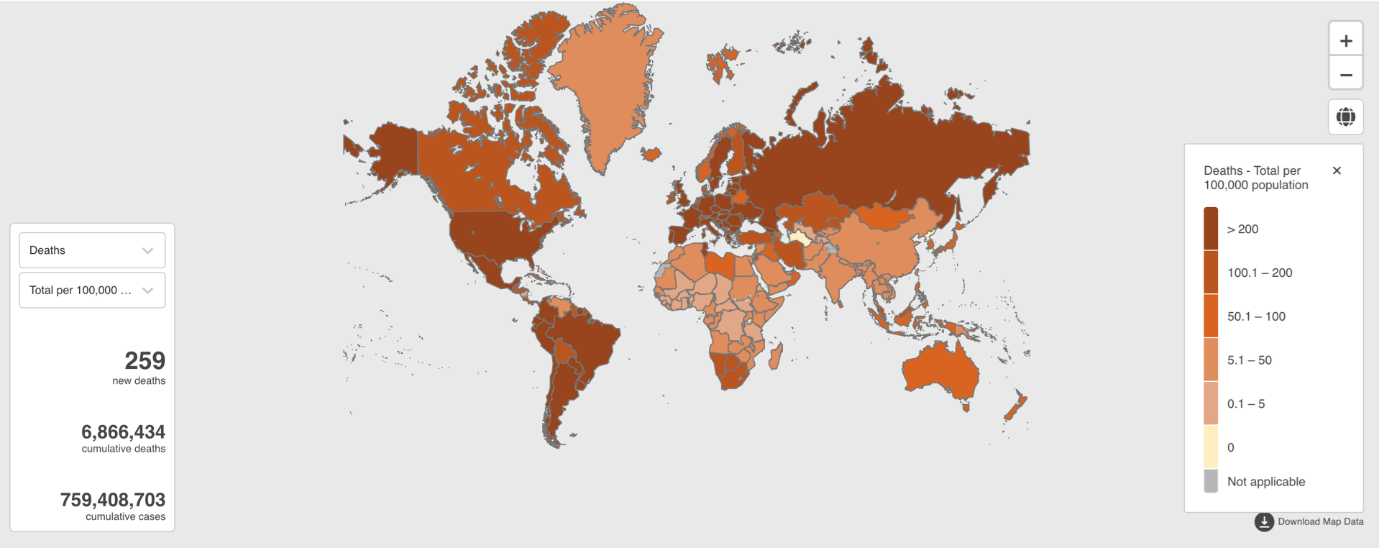

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has declared that Covid-19 is no longer a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), but it is still causing severe illness and death – and there is likely to be another pandemic around the corner. According to WHO’s Coronavirus Dashboard, the cumulative cases worldwide now stand at almost 766,000,000, with nearly seven million reported deaths.

In March the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA) and International Longevity Centre held the second of their webinars looking at the relationship between the pressing challenges of today and longevity. A range of experts were invited to explore the lessons learned during the Covid-19 pandemic and whether our ageing populations were now better prepared for the next one.

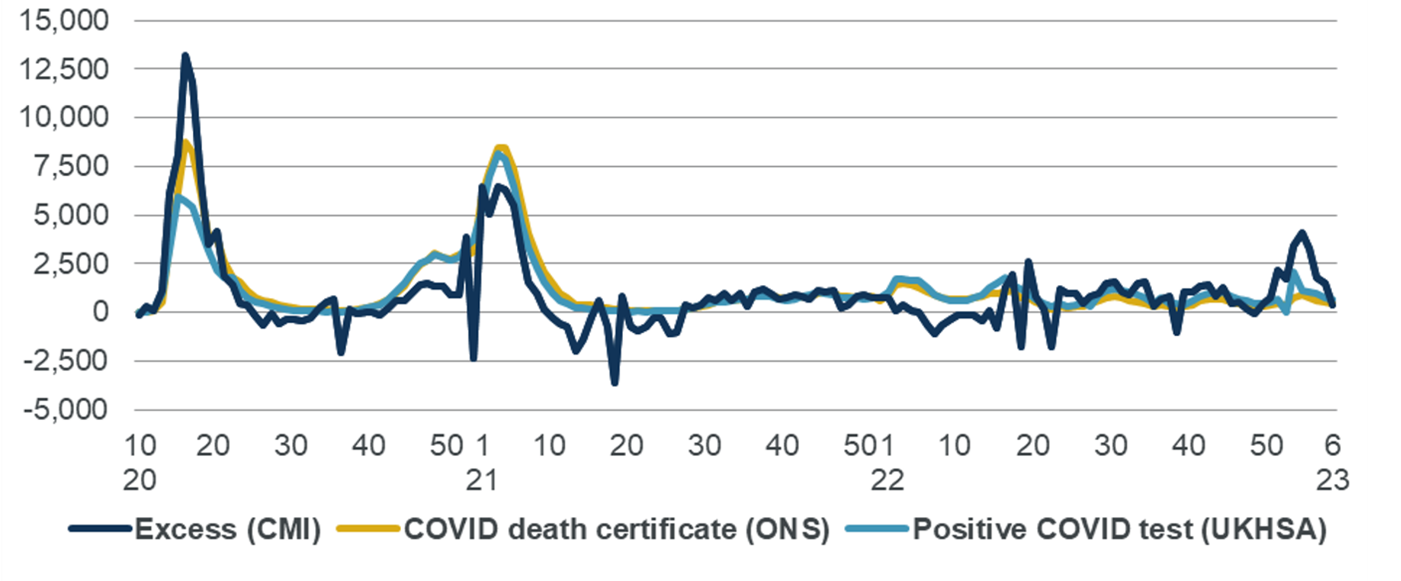

Matthew Edwards highlighted key findings from the Continuous Mortality Investigation’s (CMI) submission to the public inquiry into Covid-19. One of the CMI’s significant contributions during the pandemic was the publicly available weekly mortality monitor, which analysed excess deaths data.

The chart below shows the CMI’s measure of excess mortality compared to the number of deaths with Covid-19 listed on the death certificate published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and data for deaths of people within 28 days of a positive test result for Covid-19 published by the UK Health Security Agency. The x-axis shows the week number and year from 2020 to 2023.

The chart shows that in the first wave of the pandemic, the CMI’s measure of excess deaths was significantly higher than data published by the ONS and UKHSA, likely due to a lack of Covid-19 testing in place at the time. All three measures implied a similar level of deaths during the second wave of the pandemic.

The CMI’s analysis found that:

The CMI’s excess deaths analysis was valuable in the pandemic and has provided insights into how we can better understand mortality data in the future.

Anjana Ahuja emphasised the importance of looking at the information that was available at the time of policymaking, rather than revising history – her book Spike, jointly written with Jeremy Farrar (previously Director of the Wellcome Trust), was an account of the inside story of the pandemic.

She highlighted five key themes:

Anjana said: "We cannot leave individuals to manage on their own" and that "governments that do not take decisions are actively taking a decision not to do something, which is an important reminder that inaction can have serious consequences".

Dr Beth Kamunge-Kpodo reflecting on the title of the webinar ‘Will we survive, thrive or die next time?’ questioned who the ‘we’ being referred to was. During the first lockdown, there was a belief that Covid-19 affected us all equally. However, it is now evident that Covid-19 affects different groups unequally, based on factors such as race, gender, and class.

For example, black and other ethnic minority groups were twice as likely to be affected by Covid-19. From her perspective, longevity and the question of whether we will die, survive or thrive next time was socially constructed.

Drawing on Michel Foucault's work Society Must Be Defended1 Dr Kamunge-Kpodo highlighted how inequalities, such as racism, result in increased risk of death and what she termed ‘slow death’. This implies that people perceived as having less valuable lives are left to die slowly.

Marginalisation plays a significant role in creating poor health outcomes, as argued by Iris Marion Young.2 Therefore, we need to examine how health, education, economic and other systems contribute to creating vulnerability to premature death. The pandemic showed that health outcomes are not solely dependent on individual choices or access to healthcare. Despite the UK's free NHS, some people were more likely to die from Covid-19 than others, as evidenced by the Marmot Reports.3

Different people experience different health outcomes and mortality outcomes based on factors beyond their control, such as race, gender, and class. The government-commissioned reports by the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparity concluded there was no evidence of systemic or institutional racism in the UK, calling into question how we can prepare for racialised health inequalities in the future.

Dr. Kamunge-Kpodo remained skeptical about whether we are better prepared for the next pandemic and was concerned about the lack of intersectional approaches and the siloed nature of how we address health inequalities. For example, the housing crisis, with many people being priced out of renting, may exacerbate the impact of the next pandemic. Moreover, relying solely on medically oriented individual advice to address public health challenges may not be adequate.

Dr Kit Yates explained his research focused on examining disparities in Covid-19 infection rates and impacts, particularly among different ethnic and socioeconomic groups. “It's clear that despite claims of being in the same boat, the reality is more like some people are in super yachts while others are in dinghies.”

Three years ago, initial scientific thinking aimed to reduce the peak of infections, build up herd immunity, and protect the most vulnerable. However, it soon became clear that achieving herd immunity through natural infection was not a good idea. The Royal Society later published a report outlining the associated burden of illness and death that would come with natural infection, as well as the difficulty of identifying and protecting vulnerable individuals, and the fact that natural infection does not provide lasting immunity.

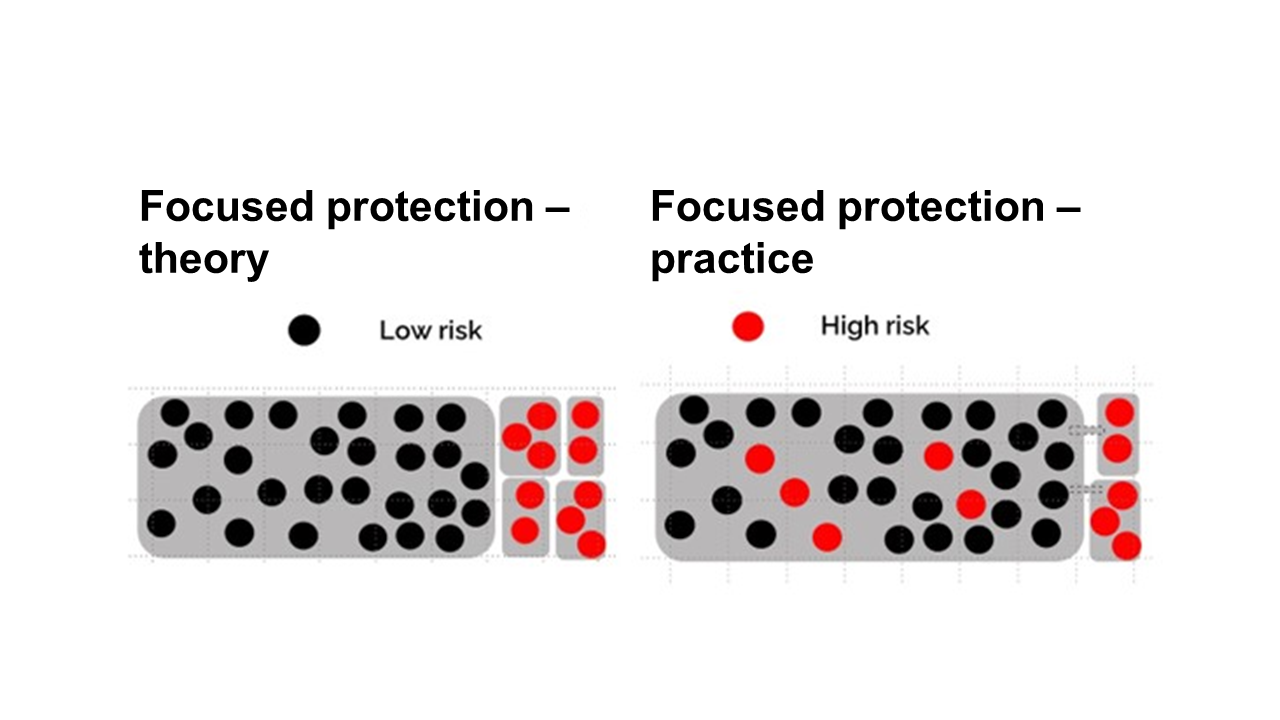

Despite this, the idea of herd immunity persisted throughout 2020, with various media reports and the Great Barrington Declaration advocating for this approach. The declaration suggested a ‘focused protection’ strategy, whereby low-risk individuals continued with their lives while high-risk individuals were shielded. However, Kit’s team at the Centre for Mathematical Biology at Bath University modelled such shielding strategies and found that, in practice, it is difficult to perfectly segregate individuals, and there are often links between high-risk individuals and low-risk communities. Therefore, a focus protection strategy may not be effective in reducing overall transmission and mortality rates.

The team explored several scenarios, including an unmitigated epidemic where everyone mixes together, a lockdown where people are segregated by households, and a focus protection strategy where high-risk individuals are completely segregated. Kit Yates said many of the mathematical models conducted provided valuable insights into the potential consequences of different policy strategies. These models clearly argued against the herd immunity strategy, and subsequent modelling has similarly shown that focus protection and shielding strategies are not practically realisable and could lead to disastrous consequences.

During a discussion on the role of mathematical modelling in pandemic response, speakers debated the limitations and benefits of such models. Matthew Edwards highlighted the value of modelling for understanding a range of factors, but also noted the tendency to focus on short-term pandemic risk models without considering longer-term impacts. There is a need for more nuanced approaches that consider broader factors beyond just disease transmission. Dr. Yates argued that modelling allows the exploration of hypothetical scenarios, but models are based on assumptions and should be critically assessed. The government's influence on the modelling subcommittee limited their freedom to model what they wanted and may have overlooked important aspects, such as economic modelling.

Professor Itamar Grotto stressed the importance of paying attention to factors that may not be easily measured or quantified, as decision-makers relied heavily on models that can be limited in their ability to account for all relevant factors. In summary, while mathematical modelling can be a useful tool for understanding potential scenarios, there is a need for more comprehensive and flexible decision-making processes that consider a broader range of factors beyond disease transmission.

Dr. Kamunge-Kpodo emphasised the need for building trust in the government's response to prepare better for future pandemics. The lack of trust was a significant issue during the pandemic, with people questioning the information and data being presented to them. The leaks and individuals disregarding rules only added to this mistrust. Even though certain groups were likely to be disproportionately affected, such as children and those without access to green spaces or housing, the government did not adequately plan or model for them, even though these consequences were predictable.

Public health scientists should be adequately consulted while making policy decisions, and transparency is crucial. The minutes of scientific advisory groups should be published in a timely manner, and information should be communicated openly and transparently. Social media can also help in promoting transparency and openness.

The issue of who was treated as expendable during the pandemic has also come to light. It is necessary to have open and honest conversations about who is being affected and how to address the inequalities. Unfortunately, the current political climate often prevents such discussions from taking place, as divisiveness has become a successful strategy for some.

Anjana Ahuja pointed out that the challenge was often in the interpretation of data and the development of effective policies. Confirmation bias can also play a role in decision-making. A framework that encourages open dialogue and acknowledges the weaknesses in our decision-making processes is necessary. Principles such as equity and caring for vulnerable populations should be prioritised. The narrative surrounding underlying conditions should not diminish the worth of those individuals in our society.

The pandemic highlighted the issue of estrangement and division in society, with the government exacerbating this through political messaging that pitched people against each other. The mischaracterisation of policies and extreme views further hindered the unity necessary to tackle the pandemic. In conclusion, building trust, transparency and openness, prioritising equity and vulnerable populations, and avoiding divisiveness are key to better prepare for future pandemics.

The speakers highlighted the lack of progress in several areas, including structural inequality, healthcare capacity, ventilation, and sick pay, and expressed pessimism about the future. Although some lessons have been learned, more needs to be done to prepare for future pandemics, as they are independent of each other, and the risk of pandemics is increasing. For example, to keep children in school, measures such as improving ventilation and air filtration are necessary, but politicians are often reluctant about such measures as retrofitting places with ventilation incurs upfront costs and does not provide immediate or tangible benefits.

Professor Itamar Grotto said the next pandemic was not a matter of if it will occur, but when. It could be caused by a new agent, mutations of current agents, or changes in the virulence of endemic agents. Mortality rates in different countries varied in response to vaccination. For example, in Israel mortality rates among those over 60 who were vaccinated were significantly lower than those who were not vaccinated.

Professor Grotto said we can learn from the Covid-19 pandemic and divide our response to the next one into three phases:

To prepare for the next pandemic, governments should focus on better prevention of the vulnerable population through vaccination against influenza, pneumococcal diseases, and Covid-19, and make better use of technology, developing improved diagnostic tools and surveillance systems. To improve our preparedness for the next pandemic at a population level there must be a renewed focus on addressing structural inequalities which undermine the ability of the individual to manage their own health.

You can watch or rewatch the debate on YouTube and see all the slides used in the presentations ILCUK website.