Sandy Trust, Former Chair of the IFoA Sustainability Board and Group Director of Organisational Risk at M&G, explains why climate tipping points are a cause for concern and why action needs to be taken now to start mitigating the effects of climate change.

Sandy Trust, Former Chair of the IFoA Sustainability Board and Group Director of Organisational Risk at M&G, explains why climate tipping points are a cause for concern and why action needs to be taken now to start mitigating the effects of climate change.

In Climate Emergency – tipping the odds in our favour, the IFoA has partnered with Sir David King’s Climate Crisis Advisory Group (CCAG) to bring together climate scientists who can speak truth to power (a rare breed) with the actuarial profession that has expertise in risk, uncertainty and finance skills at its core. This is a powerful combination and a necessary intervention to accelerate the policy action required, with climate change happening more quickly than expected and driving severe impacts globally.

The background

Our civilization emerged during a period of unusual climatic stability. In the 10,000 years prior to the industrial revolution global temperatures were relatively stable – within about 0.5˚C of the global temperature at the start of the industrial revolution. We have now exceeded this level of warming, with a global temperature rise of 1.2˚C.

We now control the greenhouse gas (GHG) levels in the atmosphere and so the ongoing stability of the climate as well. Our emissions have tipped the planetary carbon cycle out of balance, causing GHG levels to increase and temperatures to rise. What is unprecedented, as far as we are aware, is the rate of change of atmospheric GHG levels that we are causing. Without doubt, further global warming will occur due to the current levels of GHG in the atmosphere, driving more severe impacts to which we will need to adapt.

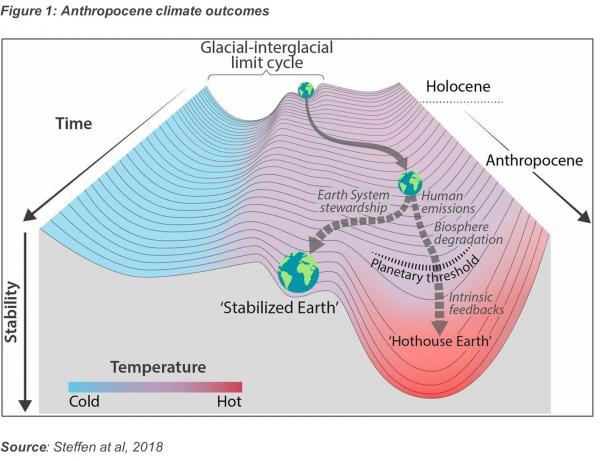

If we are not able to mitigate climate change by reaching net zero and beyond, we run the risk of pushing the Earth system past a point at which we could successfully adapt. We might trigger a series of climate tipping points that would push the planet into a ‘Hothouse Earth’ state unprecedented in human history, pre-history and beyond, as illustrated below:

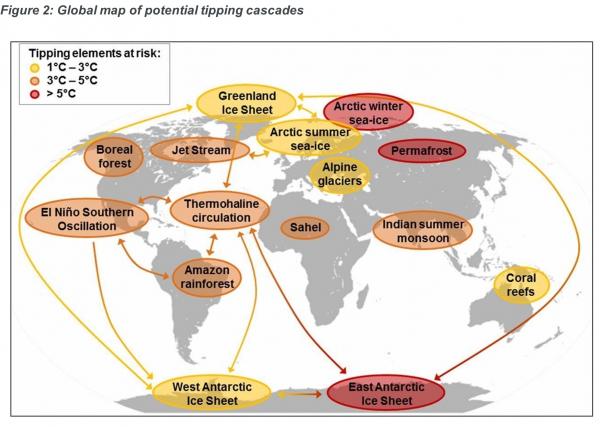

Climate tipping points can be grouped according to the estimated temperature at which they would be triggered. The risk is that tipping points triggered at lower temperatures could then contribute to the triggering of larger, more severe tipping points, particularly when combined with additional factors, setting out a cascade that would push the Earth system into a significantly hotter state. At 1˚C of warming we are already seeing significant reductions in glaciers worldwide, coral-reef bleaching, significant Greenland ice-sheet melt and Arctic summer sea-ice reduction.

Consider the impact of just two of these factors in combination: melting glaciers and heatwaves. In the region of two billion people rely on meltwater from the third cryosphere – the Himalayan icecap – for irrigation and drinking water. What would happen to these people if the glaciers melt and the water stops flowing?

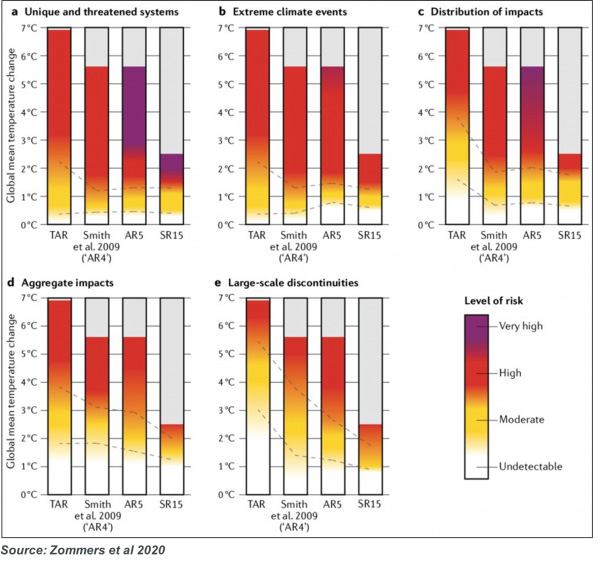

Worryingly, scientific estimates of the temperature at which severe climate impacts will occur have consistently reduced over time, as illustrated in Figure 3 below. The analysis in the Burning embers paper, shows that events that for some categories were considered high impact at 7˚C are now considered very high impact at a little over 2˚C.

Figure 3: Burning embers – IPCC risk levels at given temperatures over time increasing

We can add to this distressing analysis the probabilistic nature of carbon budgets. As detailed in the position paper of the Climate Crisis Advisory Group (CCAG):3

“The latest assessment from the IPCC indicates that around 320 billion tonnes (Gt) of CO2 can be emitted from the beginning of 2022, to have a 67% chance of staying below 1.5°C, and 420 Gt can be emitted for a 50% chance.”

With current emissions running at 40 Gt per annum we have eight years of budget left before we blow past 1.5˚C levels. This budget gives a 2/3 chance of success, so a 1/3 chance of failure. Poor odds to take for crossing a road, mad odds to use when running a planet.

CCAG go on to summarise the level of uncertainty associated with these carbon budgets and the very real risk that they may be smaller than advertised, even for these relatively low probabilities of success (my emphasis):

“There are a large number of uncertainties that impact upon estimates of the remaining carbon budget. The figures above assume strong action on non-CO2 emissions, no big shift in the AMOC [Atlantic Meridonial Overturning Circulation], and that we do not cross any unexpected tipping points; in other words, no surprises. Further, this would only provide a certain probability of remaining below 1.5°C: there is a possibility that the remaining carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5°C is already zero.”

But these underlying assumptions do not hold. There has not been strong action on non-CO2 emissions, methane levels are at an all-time high, tipping points have been partially triggered at 1˚C and deforestation equivalent to adding the annual emissions of India is taking place.

The consequences of this are to effectively either reduce the probability of success for a given carbon budget or to reduce the carbon budget for that probability of success, reinforcing the need to ‘race to zero’ as rapidly as we possibly can.

The solutions

At one level climate action is simple – reduce the level of GHGs in the atmosphere. In practice, this means reducing our emissions today as rapidly as possible, removing GHGs from the atmosphere and repairing natural carbon sinks to enable a stable climate.

We must reduce emissions urgently, deeply and rapidly, while ensuring an orderly, just transition. To help restore climate stability, the emission of CO2 and other greenhouse gases (GHG) – such as methane – into the Earth’s atmosphere must be drastically reduced from the current level of more than 40Gt CO2 equivalent per year (Gtpa) – consistent with an ordered and rapid withdrawal from fossil fuels globally.

We must remove CO2 from the atmosphere in vast quantities – tens of Gtpa. Additional efforts to test and deploy GHG removal solutions must also start today. And the target must be set at limiting temperature rise to 1.5°C – only reducing from there.

We must repair broken parts of the climate system, starting with the Arctic, in an attempt to reverse local changes, and stop the cascade effects of said changes through global climate systems.

As damage done to the Arctic by rapid climate change is causing weather patterns to shift all over the world, it is now the most urgent area to be addressed and repaired.

Critical enablers include enhanced governance, social justice and carbon literacy for decision makers and stakeholders.

Government policies will drive emissions reductions, as supportive policies will be critical to supercharging the rate of uptake of climate solutions. The financial system will be an important enabler of successful adaptation and mitigation, with an important role for actuaries.

Reasons for hope

There are compelling reasons to believe climate action can be accelerated, linked to the positive tipping points that are starting to emerge in our global society.

These include changing beliefs on climate action, the rate of technological innovation on climate solutions, having nature as a powerful ally and perhaps, above all, the recognition that as a species we have agency here. It is within our collective capabilities to steer our future back onto a safe course and we must make every effort to do so – we are all climate activists now.

1 Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene

2 Burning embers: towards more transparent and robust climate-change risk assessments | Nature Reviews Earth & Environment

3 https://static1.squarespace.com/static/60ccae658553d102459d11ed/t/6253f… sitionPaper_CriticalPathway.pdf