As the UK population continues to age, albeit more slowly than previously, can our pensions system properly support us in the years to come? In June 2023, the International Longevity Centre UK and the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries held a joint webinar to explore this question. And here Emily Evans, ILC’s Senior Communications and Engagement Officer reflects on the discussion.

As the UK population continues to age, albeit more slowly than previously, can our pensions system properly support us in the years to come? In June 2023, the International Longevity Centre UK and the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries held a joint webinar to explore this question. And here Emily Evans, ILC’s Senior Communications and Engagement Officer reflects on the discussion.

The human right to a pension and the financial feasibility of it for the Treasury and taxpayers is a balancing act. John Cridland’s 2017 report recommended advancing the state pension age from 67 to 68 by 2039, 7 years ahead of the original plan, to save 0.4% of GDP. Without changes, he said, the UK would be spending over 7% of GDP on pensions by 2066, up from just over 5% five years prior.

In the recent second review, Baroness Neville Rolfe had more evidence of the longevity slowdown, exacerbated by the pandemic. So, while the government's decision to pause and reassess the situation might be welcomed by some, in the long term, the ILC believes it is inevitable most people will be getting their pension later than previous generations.

The ageing society's impacts are mostly inevitable. Today, we have 1.7 million people over 85. In 50 years, this number will rise to 4.7 million. The state pension costs over £100 billion a year and has increased 3-fold since 2000. By 2040 there will be more than 17 million people aged 65 and over, 4 million more than today and so these costs will rise even further. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has suggested that delaying the increase by 7 years is likely to cost over £60 billion.

The former Pensions Minister, Steve Webb, agreed that the decision to hold off on accelerating state pension age increases was appropriate. However, he disagreed with the suggestion in Baroness Neville Rolfe's report to cap state pension at 6% of national income, as it could lead to drastic measures such as increasing the pension age or scrapping the triple lock.

Has there been a noticeable increase in people receiving benefits because of the rising state pension age?

A universal state pension age is beneficial as geographical or employment variations will create additional complexity and uncertainty but may disadvantage individuals who struggle to work longer. Such individuals may struggle to earn a significant income in middle age, and an increase in state pension age could impact them greatly. John Cridland’s SPA review suggested means-tested pensioner benefits a year before state pension age for long-term carers and those with health issues or disabilities. However, this was not favoured by the IFoA, as it would delay state pensions for those who can continue to work, while the disadvantaged could access means-tested benefits earlier.

When discussing pensions, longevity is a crucial factor, particularly concerning costs. From an individual's standpoint, there's a significant concern: will my funds last for the duration of my life? Additionally, some question the value of their pension if they don't live as long as anticipated.

While the state pension is a critical aspect of the overall pension system in the UK, Leah Evans, Chair of the Pensions Board at the IFoA, noted the system is layered, with public and private provisions interlacing differently. The public provision serves as a fundamental safety net, while the additional private, personal pension contributes to a more comfortable retirement.

Traditionally, many UK residents enjoyed generous defined benefits (DB) pensions, complemented by a state pension. However, increased life expectancy has escalated employer costs, driving a significant transition towards defined contribution (DC) pensions. ILC analysis shows that one third of Generation X could face inadequate retirement income due to this transition, a risk likely to increase for future generations.

A significant issue with DC pensions is adequacy, with many unable to contribute enough for a desired retirement income. Furthermore, they shift risks, such as longevity, onto individuals. The ILC’s latest research on spending habits reveals difficulties people face predicting future needs, impacting the economy, spending habits, and workforce. Most retirees are cautious spenders and unlikely to rely on welfare benefits. Hybrid post-retirement products combining drawdown and annuities could help them to sustainably enjoy savings.

Leah Evans argued against drawdown limits and for improved pension education and advice, whereas Sue Lewis argued that the industry does not explain pensions clearly enough to non-experts, and while not sufficient on its own, more financial education is needed.

Research by the IFoA includes a focus on the decumulation phase of retirement. This involves exploring the optimal way to manage retirement income from diverse sources, which could include a blend of drawdown, individual annuities, and longevity pooling. Making these systems functional and comprehensible and addressing the private sector pension issue should be a priority for government policy.

20 public service pension schemes are under the purview of the Government Actuary’s Department (GAD), covering sectors from the NHS to the judiciary. providing retirement benefits for 50 million members, with annual disbursements of £50 billion.

As Owen Dimbylow, who leads the GAD team advising the Treasury on public service pensions policy explained, the demographic changes we are witnessing could significantly impact these pension schemes' sustainability.

Most public service pension schemes, except the local government pension scheme and state pension payments, operate as unfunded pay-as-you-go arrangements. Contributions from active members are used to pay pensions to those in retirement, with balancing payments addressing shortfalls. Contributions aren’t ringfenced but directed into general government coffers.

GAD’s 2020 Quinquennial Review of the National Insurance Fund predicted an increase in state pension recipients due to demographic shifts. To balance contributions and benefits, National Insurance contributions would need a near 12% increase by the 2080s. If no changes are made, the fund could deplete by 2043 to 2044, necessitating adjustments such as increased National Insurance contributions or changes to the state pension age, benefit levels, the triple lock, or government funding.

Owen Dimbylow said demographic impacts on public service pensions depended on workforce size and political decisions. For instance, increased demand for healthcare due to an ageing population may boost active members in the NHS scheme. Public service schemes undergo regular actuarial valuations to set employer contribution rates. Measures to enhance scheme sustainability include linking the normal pension age to the state pension age in some schemes and a cost control mechanism adjusting benefits to maintain target costs.

Steve Webb argued that comparing state pension costs to National Insurance revenue, which can fluctuate, was pointless, as the Treasury can top up the fund. He also contended that, given the pressures of health and social care, the sustainability of public service pensions is of lesser concern.

There are further challenges for future generations ahead. Having joined the job market too late to benefit from final salary pension schemes, yet too early to benefit from auto-enrolment into a workplace pension, many Gen Xers (those born between 1965 and 1980) face inadequate retirement incomes.

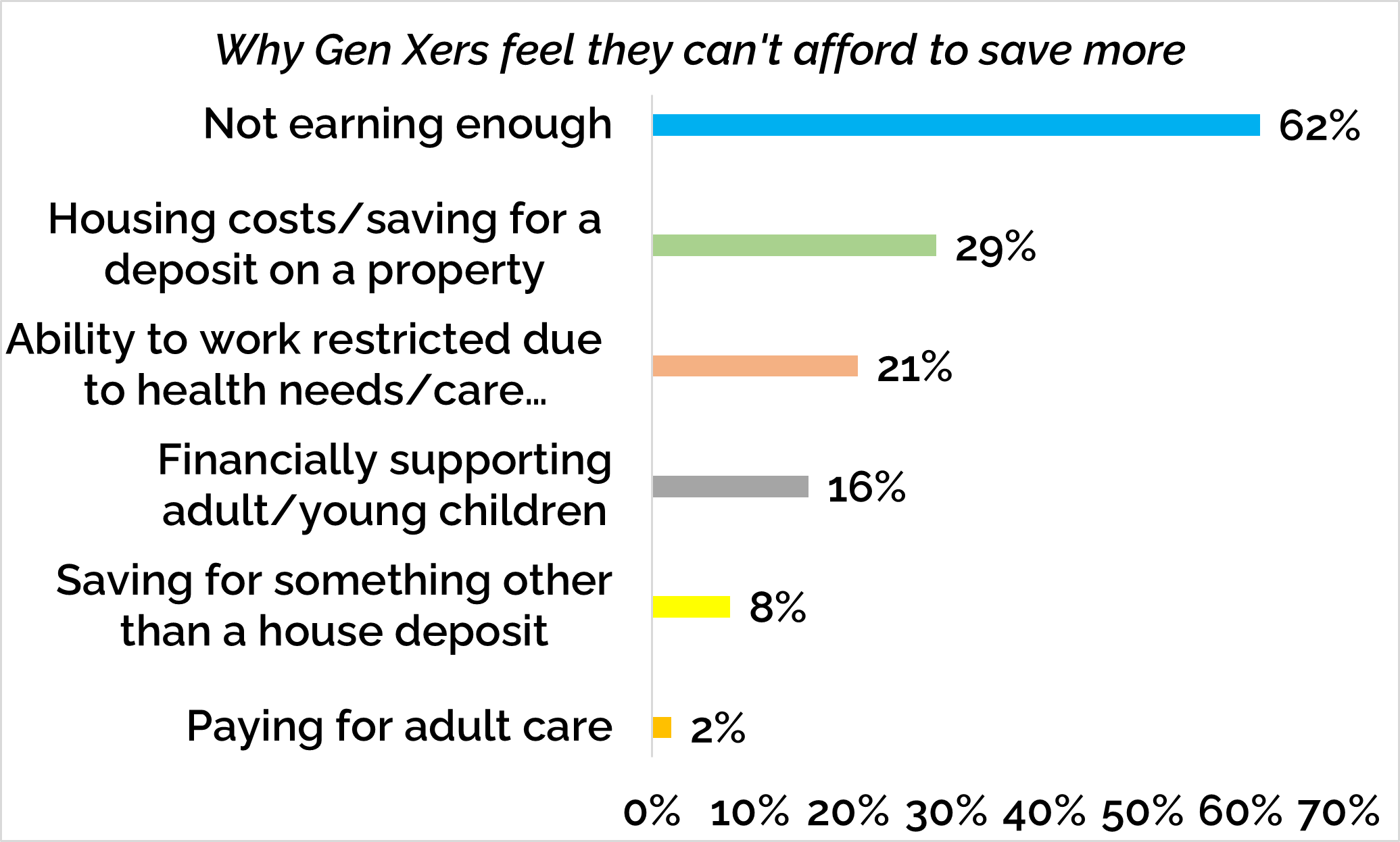

Lily Parsey said ILC’s 2021 research revealed that about one third, or 4.3 million, of Generation X risk reaching retirement with minimum incomes. With a window of opportunity shrinking in the next 10 to 15 years, interventions are necessary. The financial struggles are amplified for Gen X women, with one in 6 reported having no pension savings at all.

Implementing flexible working hours to accommodate caregiving responsibilities could enable more people to work. Granting 10 days of paid leave for caregivers could also provide much-needed relief.

Extending auto-enrolment to those who currently don't qualify would help significantly, along with greater flexibility through 'sidecar' saving schemes. Also, increasing awareness and uptake of free appointments like 'Pension Wise' at age 50 could help people plan better.

Statistics from the IFS show while pensioners are faring well currently, the future isn't as promising. The upcoming generation of DC retirees will have insufficient pensions, with women, on average, having smaller pensions than men. In the future, the state pension will be crucial for women and lower-income retirees. Steve Webb said that if we discard the triple lock, we risk increasing gender pension inequality and pushing more people into poverty. We may need to reconsider the triple lock in the future, but for now, it provides a solid foundation.

The plight of low-wage, high-turnover workers in hospitality, retail, and similar sectors needs serious attention. They are going to struggle in retirement, relying primarily on the state pension.

Before the introduction of pension credit, older people were more likely to be poor than younger people. This trend has been reversed, but now with the end of DB pensions, we're likely to see a rise in pension poverty again. The challenge for us is how to maintain this success while ensuring intergenerational fairness.

John Cridland suggested redefining jobs for older workers to focus more on knowledge and experience. A ‘midlife MOT’ could help us prepare for life's third stage, but there will always be those unable to work due to health, poor employability, or caring responsibilities.

There has been a decline in discrimination against older workers, but it's still challenging for older individuals to re-enter the job market. More flexible job contracts would help allow people to work part-time or around their caring responsibilities and physical capabilities.

Analysis of the ILC’s Global Healthy Ageing and Prevention Index reveals that EU workers, on average, work 28 years in their life, compared to 31.5 years in the UK. David Sinclair said to help our economy adapt to longer lives we needed to boost the average number of working years to a level comparable to that in Scandinavian countries. This didn't necessitate working till 70 or 75 but gradual increases to average retirement age.

State pension age debates tend to favour the Treasury and public finances over the well-being of older people. Unfortunately, adult social care seems to be continually deferred. It's a significant issue as some people will incur minor care costs, while others could face substantial costs. We can't predict who falls into which category. This isn't an issue that can be solved by individual savings; we need a collective solution.

The current premise of the pension system – that retirees need less income – is based on outdated assumptions such as the expectation that mortgages will be paid off by retirement. Today, however, younger generations may retire without owning a home, incurring additional costs. As people live longer, the need for care increases.

While the flexibility of freedom and choice in early retirement is attractive, the prospect of managing an investment pot and predicting lifespan at 80 is daunting, especially for those in the DC generation at retirement. Steve Webb suggested that annuities could be beneficial, not at 65 where pension freedoms are crucial, but later. A 'flex first, fix later' approach could offer initial retirement flexibility followed by an annuity, with individuals having the option to opt out.

Collective defined contribution (CDC) pension schemes pool savers' money into a single fund for annual pension income. Panel members appreciated CDCs as a potential solution, especially multi-employer schemes for job flexibility and post-retirement CDCs for lifelong payout, mitigating longevity risks. However, clear communication was crucial for members to understand the system, including potential benefit changes and exit options.

Owen Dimbylow felt tax relief was an important tool for encouraging pension saving, however, it should be administered fairly. Steve Webb believes pension tax relief could be used more efficiently with a separate approach for DB and DC pensions. For DC, we need a system that offers matching for low earners. For instance, for every £1000 they put in, the government should match it, decreasing the match rate as contributions increase. This approach favours low earners who often under-save for pensions.

To conclude panellists said what was needed was a greater focus on:

We need to sustain a state pension system that provides reasonable pension ages, address the individual's massive uncertainty about longevity, and avoid being side-tracked by public service pensions. Longer life means longer work periods but, with careful thought, we can turn this into an opportunity.

The pensions and longevity webinar was chaired by Sue Lewis, Chair, Consumer Advisory Board and ILC Trustee.

Speakers included:

To watch a recording of the debate on YouTube, visit: Pensions and longevity: Provision for an ageing population